*Disclaimer – the following is a research paper by author of this blog for her degree in Religious Studies at Arizona State University

(REL 407 ASU Capstone – Religious Studies)

Abstract Society’s relative knowledge of culture’s evolution has unfolded further as we discover new biblical pieces that fit in antiquity. Challenges arise as we try to place these puzzle pieces back into where they were formed. As innovative technology and antiquity understandings emerge, it is crucial to revisit where artifacts may or may not belong. The dry air of the Mediterranean’s mid-region has preserved a sizable portion of the Coptic text of the Gospel of Mary. At the same time, the echoes of earlier Greek versions barely left scholar’s scraps of papyrus. The purpose of this study is to provide a fresh and objective look at the Gospel of Mary and present evidence to potentially shift the document into the category of early Christian studies, rather than the information being viewed in connection exclusively with the current Gnostic grouping. Suggestions from scholars, skews in paleography data, geography, along with new carbon-14 data curves discovered in 2013, the Gospel of Mary manuscript pieces written in Greek will register the placement in the first-century era. With the Gospel of Mary’s Greek fragments being potentially measurable in the first-century timeline, the more extensive Coptic text version will be examined next to the canonical authors to establish a high percentage of similar themes and topics. An additional survey will provide data from 12 countries and how 192 people view the Gospel of Mary in comparison to the New Testament. The survey data implements that the Gospel of Mary reading interests a higher percentage than the New Testament, even with a higher number of Christian respondents. The Gospel of Mary evidence can provide new cultural navigation of early Christian groups and improve understanding of current texts in the canonical writings. The Gospel of Mary and the canonical New Testament will favor both being an early Christian theme and a cultural worldview of modern Christians. This study will place a gospel attributed to a woman’s name, Mary, closer to the studies of Christianity’s formation that later created a path toward the New Testament, rather than among the manuscripts found at Nag Hammadi, known as the Gnostic Gospels.

Keywords

Gospel, Mary, Paleography, Carbon-14 Dating, New Testament, Christianity, Antiquity, Archaeology, Geochemistry, Canonical, Gnostic, Nag Hammadi

Literature Review

The Gospel of Mary

In the vast region of Egypt, pieces of manuscript with a parallel message lay hidden in the dry region until the first collection was uncovered in the nineteenth century. At the beginning of 1896, a transaction was made between a manuscript dealer in Egypt and a German scholar, Dr. Carl Reinhardt. Surprisingly, this purchase awarded Reinhardt a fifth-century leather-bound codex, a book that measured 12.7 cm by 10.5 cm (King, p.9). Inside were the delicate pages offering four previously unknown works, the Apocryphon of John, the Sophia of Jesus Christ, the Act of Peter, and the Gospel of Mary (De Boer, 2004). The codex, now known as the Berlin Codex, is written in Coptic script, the last phase of the Egyptian syntax, which was practically used solely by Christians in Egypt (Depuydt, 2010). Scholars have often realized that as pieces of the written word began to fade or be in danger of destruction by humans, early Christian groups would replicate the material, which is evident as two older fragments of the Gospel of Mary were discovered written in Greek (Erhman and Plese, 2011) (King, 2003) (De Boer, 2004). These two pieces, now known as Papyrus Rylands 463 (PRyl) and Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 3525 (POxy), contained a small portion of words that correlate almost precisely with the more significant Coptic portion of the Belin Codex (King, 2003). Pinning down the date of these two fragments has not been easy, many scholars cannot agree upon a timeline to satisfy all academia. Karen L. King, in her book, The Gospel of Mary Magdala, mentioned these pieces being dated in the early third century but suggested it could be earlier, possibly first-century, in a later interview (The Pell Center, 2019) (King, 2003). Esther De Boer explains that scholars suggest the Greek fragments date to the second century based on women’s leadership and the Middle Platonist themes found in that era (De Boer, 2004). However, De Boer offered the argument that she is open to believing the manuscript fragments are earlier due to the alignment of ‘imagery of the Son of Man’ with the mid-first century’s Pauline letters (De Boer, p.14).

To get a better understanding of the Gospel of Mary, the following is the translation from the pages in the Berlin Codex (King, p.13-18):

[ ] Brackets indicate where the text is missing and has been restored by scholars

Pages 1-6 are missing.

“… Will m[a]tter then be utterly [destr]oyed or not?”

The Savior replied, “Every nature, every modeled form, every creature, exists in and with each other. They will dissolve again into their own proper root. For the nature of matter is dissolved into what belongs to its nature. Anyone with two ears able to hear should listen!”

Then Peter said to him, “You have been explaining every topic to us; tell us one other thing. What is the sin of the world?”

The Savior replied, “There is no such thing as sin; rather you yourselves are what produces sin when you act in accordance with the nature of adultery, which is called ‘sin.’ For this reason, the Good came among you, pursuing (the good) which belongs to every nature. It will set it within its root.”

Then he continued. He said, “This is why you get si[c]k and die: because [you love] what de[c]ei[ve]s [you]. [Anyone who] thinks should consider (these matters)!

“[Ma]tter gav[e bi]rth to a passion which has no Image because it derives from what is contrary to nature. A disturbing confusion then occurred in the whole body. That is why I told you, ‘Become content at heart, while also remaining discontent and disobedient; indeed become contented and agreeable (only) in the presence of that other Image of nature.’ Anyone with two ears capable of hearing should listen!”

When the Blessed One had said these things, he greeted them all. “Peace be with you!” he said. “Acquire my peace within yourselves!

“Be on your guard so that no one deceives you by saying, ‘Look over here!’ or ‘Look over there!’ For the child of true Humanity exists within you. Follow it! Those who search for it will find it.

“Go then, preac[h] the good news about the Realm. [Do] not lay down any rule beyond what I determined for you, nor promulgate law like the lawgiver, or else you might be dominated by it.”

After he had said these things, he departed from them.

But they were distressed and wept greatly. “How are we going to go out to the rest of the world to announce the good news about the Realm of the child of true Humanity?” they said. “If they did not spare him, how will they spare us?”

Then Mary stood up. She greeted them all, addressing her brothers and sisters, “Do not weep and be distressed nor let your hearts be irresolute. For his grace will be with you all and will shelter you. Rather we should praise his greatness, for he has prepared us and made us true Human beings.”

When Mary had said these things, she turned their heart [to]ward the Good, and they began to deba[t]e about the wor[d]s of [the Savior].

Peter said to Mary, “Sister, we know that the Savior loved you more than all other women. Tell us the words of the Savior that you remember, the things which you know that we don’t because we haven’t heard them.”

Mary responded, “I will teach you about what is hidden from you.” And she began to speak these words to them.

She said, “I saw the Lord in a vision and I said to him, ‘Lord, I saw you today in a vision.’

He answered me, ‘How wonderful you are for not wavering at seeing me! For where the mind is, there is the treasure.’

I said to him, ‘So now, Lord, does a person who sees a vision see it <with> the soul <or> with the spirit?’

The Savior answered, ‘A person does not see with the soul or with the spirit. ‘Rather the mind, which exists between these two, sees the vision an[d] that is w[hat … ]’

(Pages 11-14 are missing.)

” ‘… it.’

“And Desire said, ‘I did not see you go down, yet now I see you go up. So why do you lie since you belong to me?’

“The soul answered, ‘I saw you. You did not see me nor did you know me. You (mis)took the garment (I wore) for my (true) self. And you did not recognize me.’

“After it had said these things, it left rejoicing greatly.

“Again, it came to the third Power, which is called ‘Ignorance.’ [It] examined the soul closely, saying, ‘Where are you going? You are bound by wickedness. Indeed you are bound! Do not judge!’

“And the soul said, ‘Why do you judge me, since I have not passed judgement? I have been bound, but I have not bound (anything). They did not recognize me, but I have recognized that the universe is to be dissolved, both the things of earth and those of heaven.’

“When the soul had brought the third Power to naught, it went upward and saw the fourth Power. It had seven forms. The first form is darkness; the second is desire; the third is ignorance; the fourth is zeal for death; the fifth is the realm of the flesh; the sixth is the foolish wisdom of the flesh; the seventh is the wisdom of the wrathful person. These are the seven Powers of Wrath.

“They interrogated the soul, ‘Where are you coming from, human-killer, and where are you going, space-conqueror?’

“The soul replied, saying, ‘What binds me has been slain, and what surrounds me has been destroyed, and my desire has been brought to an end, and ignorance has died. In a [wor]ld, I was set loose from a world [an]d in a type, from a type which is above, and (from) the chain of forgetfulness which exists in time. From this hour on, for the time of the due season of the aeon, I will receive rest i[n] silence.’ ”

After Mary had said these things, she was silent, since it was up to this point that the Savior had spoken to her.

Andrew responded, addressing the brothers and sisters, “Say what you will about the things she has said, but I do not believe that the S[a]vior said these things, f[or] indeed these teachings are strange ideas.”

Peter responded, bringing up similar concerns. He questioned them about the Savior: “Did he, then, speak with a woman in private without our knowing about it? Are we to turn around and listen to her? Did he choose her over us?”

Then [M]ary wept and said to Peter, “My brother Peter, what are you imagining? Do you think that I have thought up these things by myself in my heart or that I am telling lies about the Savior?”

Levi answered, speaking to Peter, “Peter, you have always been a wrathful person. Now I see you contending against the woman like the Adversaries. For if the Savior made her worthy, who are you then for your part to reject her? Assuredly the Savior’s knowledge of her is completely reliable. That is why he loved her more than us.

“Rather we should be ashamed. We should clothe ourselves with the perfect Human, acquire it for ourselves as he commanded us, and announce the good news, not laying down any other rule or law that differs from what the Savior said.”

After [he had said these] things, they started going out [to] teach and to preach.

[The Gos]pel according to Mary

Though the Berlin Codex offered up a more significant portion of the Gospel of Mary, approximately half of it was missing, including the first six pages and portions of the middle. Additionally, the two other smaller papyri did not solve any missing pieces but confirmed that this document had been in circulation for several hundred years. Nonetheless, from what we can read, the Gospel of Mary is a new look at an early Christian circle of characters in a post-resurrection setting (De Boer, 2004). Through the three manuscript layers, translations establish the following breakdown of the Gospel of Mary (King, 2003) (De Boer, 2004):

- Jesus was speaking to those present about the nature of matter.

- Jesus speaks of the nature of sin and the Good.

- Jesus gives a final departure.

- Mary tries to comfort the disciple characters (Peter, Andrew, and Levi) with her words.

- Peter asks Mary to teach

- Vision and Mind (soul and spirit)

- Ascent of the soul

- Disciples debate Mary’s teaching

- Disciples leave to preach and teach

The authenticity and the meaning of the Gospel of Mary are equally debated today. Nevertheless, as this study will show, this text’s placement belongs within early Christian study and not the Gnostic teachings.

The New Testament

Assumptions sometimes overlook clarification; when studying other religions, it is vital to know what earlier followers had available. Therefore, it is necessary to state that the Bible’s characters did not have all the teachings of Jesus available to them in a document. However, it is also fair to state that neither do we today, as most information was lost or destroyed. Scholarship makes it imperative to know what writing and teachings belong in the New Testament.

Most followers’ information came by word of mouth or witnessing Jesus in the first century. Early Christian followers knew the only authoritative scripture to be the Hebrew Bible, similar to the Old Testament for modern Christians (Harris, 2015). The community of Jesus’ followers produced several early writings, many authors were believed to be active around 50-140 CE, yet the first canonical list did not come together until around 367CE (Harris, p.23). The New Testament scripts were typically found in codex form, with the writing found on both front and back, making it difficult for scholars to create an earliest to the latest period for the works (Orsini and Clarrysse, p.444). No original copies of any canonical work survived, but scholars of the day were flooded with hundreds of variations that they would need to compare. Today we have 27 accepted books, or the church-approved canon, in the New Testament. Both Protestant and Catholic churches accept these selected books. Here are the names of the books found in the King James Version of the Holy Bible:

- Gospel According to Matthew

- Gospel According to Mark

- Gospel According to Luke

- Gospel According to John

- Acts of the Apostles

- Letter of Paul to the Romans

- 1 Corinthians (Letters of Paul to the Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians (Letters of Paul to the Corinthians)

- Letter of Paul to the Galatians

- Letter of Paul to the Ephesians

- Letter of Paul to the Philippians

- Letter of Paul to the Colossians

- 1 Thessalonians (Letters of Paul to the Thessalonians)

- 2 Thessalonians (Letters of Paul to the Thessalonians)

- 1 Timothy (Letters of Paul to Timothy)

- 2 Timothy (Letters of Paul to Timothy)

- Letter of Paul to Titus

- Letter of Paul to Philemon

- Letter to the Hebrews

- Letter of James

- 1 Peter (Letters of Peter)

- 2 Peter (Letters of Peter)

- 1 John (Letters of John)

- 2 John (Letters of John)

- 3 John (Letters of John)

- Letter of Jude

- Revelation to John

One can read the New Testament as it is laid out today and see a linear theme that begins with an endangered child’s genealogy and finishes with a new heaven and earth ruled by the exalted Jesus. However, the order is not placed in chronological order. Instead, the New Testament is broken into literary categories:

- The Gospels – these books layout the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus. By definition, ‘Gospel’ must contain the words of Jesus (Harris, p.13). Additionally, the Gospels are said to have been sourced from four separate sources: The Gospel of Mark and three lost sources (Q, M, and L) (Perkins, 2009).

- Acts of the Apostles – though the author of Acts is thought to be the same as the person who wrote Luke, this portion of writing takes place after Jesus’ resurrection and overviews the first church being established in the Roman Empire (Harris, 2015).

- Epistles (or Letters) – these following twenty-one books are letters, and sermons, directed toward the churches struggling to follow Jesus’ teachings. Here is where the Pauline Letters fall and chronologically are placed as some of the earliest writing in the New Testament (Harris, p.15).

- Apocalyptic – like other apocalyptic writing, and by the definition of the word apocalypse meaning ‘uncovering,’ Revelation gives John’s account of visions that are otherworldly things unseen by other disciples (Harris, 2015).

The New Testament development as we see it today did not come by way of one particular church or a formal assembly of church leaders. Like Martin Luther in the sixteenth century or even the council formed in the fourth century, key historical people played pivotal roles in what we see as the modern Holy Bible. Some scholars have suggested that the gathering of Jesus’ teachings into the New Testament began when a disciple of Paul toward the end of the first century put the Pauline letters together as a single piece (Harris, 2015) (King, 2003). Nevertheless, time had allowed the stacks of writings proclaimed to be by apostles to overflow and get lost in the shuffle. Throughout the years, various canons were created with assortments, some of which never made the final cut, including the Epistle of Barnabas that examines Jesus’ teachings of the Old Testament. Arguably, the New Testament history was influenced politically and regionally by churches, and that it was not until Christianity sat in power that influence outweighed origins. Phrases found in modern versions have been changed by errors in copying and some intentionally to steer Christian readers away from questionable phrases that show the human side of Jesus. One example that divides modern Christians today is found in a late manuscript of 1 John 5:7-8 and the nature of God. A biblical scribe places the doctrinal reference to the trinity to state God exists as three and that the three are one.; however, this idea is not found anywhere before the fourteenth century (Harris, p.31). These times of teachings change the very nature of monotheism of One God. The New Testament in its current form may not represent the early Christian writings or beliefs, making it difficult to assess if new text found in the modern-day would align with what Jesus taught.

The New Testament is a portion of what represents early Christianity decided by people centuries later, but not a complete collection of cohesive teachings. If new manuscripts can be dated and parallel the current New Testament and add a substantial increase of understanding, it should be considered equal to early Christian theology.

Gnostic Gospel’s

Gnosticism, a more modern term, is applied to a movement from around 200-400 C.E. that viewed Jesus as pure spirit and free from human fault, like oil to the water of other Christian beliefs that portrayed him as both human and God (Harris, p.241). Like most any religion, Gnosticism took many forms of creed, and no one church was called the ‘Gnostic Church’ of that day. Gnosticism’s common factor is the universe’s polarity that explains an invisible spiritual realm that is eternally pure with an equal counterpart of evil in the physical world. The Oxford Dictionary gives a simple definition of the word ‘gnosis’ as ‘knowledge of spiritual mysteries,’ which scholars applied to these groups who taught salvation from the physical world only came through ‘special knowledge imparted to a chosen elite’ (Harris, p.241) (The Oxford Dictionary, 1996). Today we have several of these manuscripts that are a creative mixture of the nature of Jesus, the afterlife, the universe, and the physical world being an illusion. Grouped as gnostic in teaching, many of these were found together at Nag Hammadi, Egypt, but the Gospel of Mary was not a part of the manuscripts found with the majority of the others. The following is a list of manuscripts, disperse through eight codices, found at Nag Hammadi, in Egypt:

- The Dialogue of the Savior (Saviour)

- The Book of Thomas the Contender

- The Apocryphon of James

- The Gospel of Philip

- The Gospel of Thomas

- The Thunder, Perfect Mind

- The Thought of Norea

- The Sophia of Jesus Christ*

- The Exegesis on the Soul

- The Apocalypse of Peter

- The Letter of Peter to Philip

- The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles

- The (First) Apocalypse of James

- The (Second) Apocalypse of James

- The Apocalypse of Paul

- The Apocryphon of John *

- The Hypostasis of the Archons

- On the Origin of the World

- The Apocalypse of Adam

- The Paraphrase of Shem

- The Gospel of Truth

- The Treatise on the Resurrection

- The Tripartite Tractate; Eugnostos the Blessed

- The Second Treatise of the Great Seth

- The Teachings of Silvanus

- The Testimony of Truth

- The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth

- The Prayer of Thanksgiving; A Valentinian Exposition

- The Three Steles of Seth

- The Prayer of the Apostle Paul

*Indicates a writing also found in the Berlin Codex along with the Gospel of Mary

Many familiar names appear on the list above, yet none are a part of the canonical selection. As mentioned in the section about the New Testament, the word ‘gospel’ contains the words of Jesus, which can be furthered to state the teachings of Jesus. We see this is the first four books of the canonical version today (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). Many listed Gnostic texts use the word gospel in their titles, but scholars over the centuries have changed the titles, while some remain that do not contain the words of Jesus, like The Gospel of Phillip. Scholars believe that this text, devoted to the spirit’s sacrament, was written by someone other than Phillip and has no placement with the term gospel. However, some like Richard Bauckham have suggested that the term ‘gospel’ should be applied only to the eyewitnesses of Jesus and close partners’ works (Bauckham, 2009). If we follow the Bauckham rule of thumb, many of the manuscripts said to be gnostic gospels would qualify with their connection to Jesus, including the Gospel of Mary.

Dating Biblical Texts

Creating a birthplace and time for an artifact is no easy task and is not done with merely one technique. Today we can use scientific methods to examine the organic material that patinas the surface, date the chemicals used on the fibers of the material (papyri and ink), the use of language, how the author pens the lettering, and even estimate age through radioactive isotopes. However, before the nineteenth century, none of these were significant when solidifying a document’s date. Often scholars had to resort to context clues given by the author. For instance, we can tell that Moses did not write all of the books attributed to him, especially knowing certain aspects were added after Moses’ death in Deuteronomy (Hayes, 2012). The bible is filled with evidence of multiple authors and later editors. When the character Luke references Mark’s writing in the New Testament, we know that Luke’s timeline coordinates based on where scholars place Mark. However, when new manuscripts like the Gospel of Mary (the Berlin Codex) and the pieces found at Nag Hammadi, scholars quickly placed their unique stories of Jesus after the New Testament authors chronologically. History had shown that the formation of the codices, experts can agree, began in the second century when the writing went from scrolls to the less impressive codex. It was not until the firth century that leather bookbinding shows up (Funk, 2015).

Scholars have dated manuscripts based on the language used and how the dialect and descriptions are applied. The technique is only applicable to the content of the manuscript, not the ink or the papyri. Paleographers educated in ancient writing studies are often used to date manuscripts to a particular era based on evidence of the document’s writing form and other details like whether it was written on a roll or cut pieces (Turner and Parsons, 1987). The first codex found with the pages of the Gospel of Mary was in a leather-bound book, which was not an early-era practice as mentioned. However, the fragments found later show evidence of a single papyrus from a roll, which implies an earlier time. Experts will provide as much information to establish a general timeline for documents, but admittedly note that dating manuscripts 300 B.C.E. or earlier are not as easy to establish due to the comparative text not being readily available (Van Minnen, 2006). New work by scholars like Karen King, Esther De Boer, David Brakke, and others took these assumptions of manuscript timelines and revisited them using new information to place documents in new eras potentially.

Carbon-14 Dating

The simplest way to explain radioactive carbon dating without a seven-week course is to describe what equilibrium means regarding organic plant life and a specific isotope. The science behind this is straightforward but can be confusing; therefore, all the terms are not required in this paper. The key takeaways are how it works and how it can be adjusted with new data.

As most learned in science class, plants, for the most part, consume the air outside, including what we exhale and what the atmosphere provides, part of the process known as photosynthesis. The atmosphere is filled with elements charged by the sun, including carbon. Typically, carbon-12 is stable, but it is unstable or radioactive in a solar atmosphere like here on Earth. The radioactive isotopes, commonly known as carbon-14, instantly begin decaying in the atmosphere. As plants take in the atmosphere, they also take in carbon-14 until the plant dies. Dead organic material is used in making practically everything. The food chain circle allows humans to absorb these radioactive isotopes when we ingest food. This technology helps many branches of study date events in human history, including when papyrus’ organic material was made. Science continues to fine-tune the measurement of timelines based on when the organic material stopped absorbing carbon-14. Sophisticated carbon dating tools typically date items as far back as 30,000-50,000 years; after this, another form of geochronology can be used (White, 2015).

Understanding equilibrium, or balance, is essential when establishing the carbon-14 ratio in dating artifacts and manuscripts. Equally, it is vital to know what can alter older data. The data comes from two main variables, an unstable carbon atom (carbon-14) being constantly produced in a solar atmosphere and the number of plants in the season to absorb it. Not enough plants due to a drought or other factors will alter the data for several years. When data is presented, ±5 years is typically attached due to unknown factors and imbalanced ratios not accounted for in the testing (Manning, Griggs, Lorentzen, Ramsey, Chivall, Jull, Lange, 2018).

Carbon-14 dating is not the only scientific way to date items from antiquity. It is also possible to analyze it by measuring ink ingredients that change over time (Bügler, Buchner, Dallmayer, 2008). An article describing ancient Egyptian painted pieces being subjected to pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (PY-GC-MS) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) resulted in evidence of wax-based- and animal protein-based pigments (Chiavari, Fabbri, Galletti, 1995). Areas resourced different pigments, solvents, and minerals to create writing supplies, and technology is beginning to date these to specific times in history.

Evidence

Authenticity of Artifacts is Not Unanimous

The general public may think that scholars agree on everything and that there is one way to see the view of academia when discussing antiquity; however, the opposite is true. Not all experts are on the same page with artifacts. From language to radioactive carbon dating, there is a variant of opinions. As mentioned previously, the task of dating artifacts is not done with one technique, and for a good reason, not all agree or work. For example, in 2002, a mysterious discovery came to the surface through a reputable epigrapher, causing a tornado in the world of paleography and biblical artifacts (Byrne and McNary-Zak, 2009). The item of interest in question was an ossuary with the inscription ‘Ya’akov bar Yosef akhui di Yeshua,’ translated as ‘Jacob (later known as James through translations), son of Joseph, brother of Yeshua,’ or known as Jesus through modern translation (Crotty, p. 425). The burial box stirred up the world of Christian curiosity and fooled the top paleographers and scholars for quite some time. Three years later, a trial was held against those involved for potentially selling fake artifacts and theft of property. Experts, including those who specialize in depicting the writing from particular timelines, scientific experts on carbon-14 dating, and geochemists, posed standings on the authenticity of the carving on the side of the ossuary. After nine years, the Israeli judge over the case, who has a degree in archaeology, expressed that if the experts could not agree if the artifact is authentic, “how could he be expected to make a decision” (Crotty, p.425). Studies on the ossuary have continued as new technology and understanding of the ancient data develop. In time these processes will be more precise and easier to utilize by experts. The issue of the James ossuary was not if it belonged to Jesus of Nazareth, which would be nearly impossible to prove with the number of men with similar names in the first century, but rather if the artifact was or was not a modern forgery.This example illustrates that even with the assumption of forgery, scientific methods of deciding a conclusive stance of an artifact may not exist across experts’ opinions currently. The understanding that there is room for error should not cast doubt on all dating techniques but rather reweigh multiple facets that direct the timeline of an artifact if doubt is present. These interpretive thoughts of artifacts from antiquity bring to light the Gospel of Mary with how the three versions are dated and portrayed. As more artifacts are discovered and technology advances, it is imperative to reexamine fragments like the two Greek papyrus of Mary’s gospel to establish a better timeline.

New Carbon-14 Data Curve

Science currently takes humans past the timeline of the Garden of Eden, causing modern Christians to build an unyielding wall against carbon-14 dating data. Equally, as most publish their findings, carbon dating has held strong confidence in the archaeology field to date organic material. Experts have created data curves that apply to specific global areas; however, recently, archaeologists at Cornell University have discovered an error in applying this data curve to the world’s southern Levant area. Measurements of a ‘substantive and fluctuating offset’ in the radioactive isotope carbon-14 (C-14) ages and the organic material in these areas were affected by different climate cultures (Manning et al., 2018). Before these findings, the southern Levant was included with the Northern Hemisphere data curve when measuring C-14 and was included in the debate of archaeological dating of items in the Biblical period (Manning et al., 2018). Areas that are a part of the Levant region are Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey. However, even though Manning and his colleagues are currently focused on portions of the southern areas during the early Biblical periods around 1200-600 B.C.E, Manning stated that their findings might change the debate of artifacts dates found in these areas with other biblical timelines (Manning et al., 2018). The explanation for these fluctuations is inconsistent growth seasons, periods of drought, solar activity changes, and ocean circulation Manning et al., 2018). Cornell’s research team sent their samples to two laboratories. It came back with two different yields (Arizona lab= 20.6 +4.5 years and Oxford lab= 19.1 +2.8 years), however when the mean is applied to this data, it is 19 +5 years of offset, but the C14 appears to change over time (Manning et al., 2018). The findings are essential to the relevance of the C.E. era as they create new potential for items potentially dated in the late first century, or early second century, to be moved closer to the mid-first century. Significantly, the Gospel of Mary fragments written in Greek have been placed in the late first century by scholars like Esther De Boer and Karen L. King without updated carbon dating techniques. Potentially placing the Gospel of Mary in the same era as the canonical writings of the New Testament does not solidify that it is an early Christian text, only that it occurred during circa Jesus of Nazareth. With plausible evidence showing that the Gospel of Mary fragments could be old enough to have come from the first century, the content of the pages will need to align with what those close to Jesus went forth and spread as Christian teachings.The team on this project is Sturt Manning, the Goldwin Smith Professor of Classical Archaeology in the Department of Classics and director of the Cornell Tree-Ring Laboratory Cornell; Tree-Ring Laboratory senior researcher Carol Griggs, Ph.D.; and postdoctoral researcher Brita Lorentzen, Ph.D.; Christopher Bronk Ramsey and David Chivall of the Oxford University School of Archaeology; and A.J. Timothy Jull and Todd E. Lange of the University of Arizona’s Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory.

The Gospel of Mary and the New Testament Themes

As previously mentioned, the standard for the gospel definition requires that the writing contain the words of Jesus. One can note after reading the Gospel of Mary that the core of the text is attributed to Jesus’ teaching directly to the disciples or Jesus giving new teachings to Mary to share with the disciples. The first section (after the missing six pages) is Jesus speaking with either all or a portion of his disciple’s post-resurrection. Those who are named Mary, Peter, Andrew, and Levi, appear as New Testament characters. The scene is familiar to the Gospel’s and other post-resurrection settings after Mary sees Jesus in the garden (morning) and Jesus visits the disciples (evening). Karen King states that the teaching is radically different by interpretation, but personal study finds these teachings familiar to the words Jesus spoke in other biblical writings. The following is a breakdown, created for this study, of the themes/topic that appears in the Gospel of Mary. The interpretation used for comparison is from Karen L. King, as previously shared in the Gospel of Mary section of this research. However, the comparison was personally developed by me for this study to show evidence that the Gospel of Mary corresponds more with the New Testament than original ascribed.

| Topic or Theme in the Gospel of Mary | Interpretation (From King translation) | New Testament Parallels (All referenced from KJV Holy Bible) |

| Characters (mentioned by name) | Mary (female follower of Jesus), Peter (Simon), Andrew (Simon Peter’s brother), Levi (Son of Alphaeus) | All characters found in the New Testament stories as disciples. |

| Post-resurrection Setting | A time when the disciples (unsure of the count) were gathered after the resurrection, Jesus spoke with them and told them to go ‘preach the gospel of the Kingdom.’ Jesus departs. | Mark 16:9-11 – Verses that describe a brief but familiar setting to the Gospel of Mary.John 20:1-23 -Verses that begin with the appearance of Jesus the morning Mary saw him in the garden. Goes into the evening when the disciples see Jesus post-resurrection as well. |

| Nature of Matter | Open dialogue between Jesus and the disciples to know if ‘matter will be utterly destroyed or not?’ Jesus explains that nature is resolved back to its roots | 2 Peter 2:12 – Verse speaks of the nature of evil that shall ‘utterly perish’ |

| “He who has ears to hear, let him’ (verse is said two different times) | Teach all that will listen, which differs from Gnostic practices of only elite are given special teachings. | Matt 11:15, Matt 13:9, Matt 13:43, Mark 4:9, Mark 4:23, Luke 8:8, Luke 14:35, Rom 11:8, Rev 2:7, Rev 2:11, Rev 2:17, Rev 2:29, Rev 3:6, Rev 3:13, Rev 3:22 – Each of these verses state the same command to let those hear that have ears. |

| Nature of Sin | Jesus is asked by Peter ‘What is the sin of the world?’Jesus replies ‘There is no sin, but it is you who make sin…’ | John 1:29 – Verse claims Jesus took on the sin of the world1 Peter 2:24 – Verse explains Jesus bore the worlds sins so it would not die to sin but live in righteousness.1 John 2:2 -Verse states Jesus is the ‘propitiation’ for the sins of the world.1 Cor 15:3, Gal 1:4 – Other verses that mention Jesus dying for the world’s sins |

| ‘Go and preach the gospel of the Kingdom’ | Right before Jesus departs, he tells those present to preach the gospel of the Kingdom, and not to give laws beyond what has been given by Jesus. | Matt 10:7 – ‘Go, preach…kingdom of Heaven is at hand.’Luke 9:60 – Jesus said unto him, ‘…but go thou and preach the kingdom of God.’ |

| ‘They wept greatly…’ Mary turned their hearts to Good. | After Jesus tells those present to go and preach, they are grieved and weep. They are discouraged of how to proceed with teaching. At this point Mary begins to tell them what Jesus has taught her in a vision. They did not accept her words at first. | Mark 16 – Starting in verse 9 until the end of the chapter, the familiar story of the disciples weeping, Mary telling them she spoke with Jesus, and disbelief, all appear but in a different order. |

| Mary’s Vision | Mary claims to have seen Jesus in a vision, that He explains this is possible not by the soul or the spirit, but by the mind that is between the two | Matt 22:37, Mark 12:30 – Jesus states a separation of three: heart, mind, and soulVisions that produce teachings occur often in the New Testament. People like Paul, Ananias, are people mentioned to have received visions. The Book of Revelation is John’s vision of a unique description the universe. |

| The Four Powers, and the Seven Forms | The majority of Mary’s vision speak of Jesus experience past the veil. A portion is missing, but from what remains there are four powers, and the fourth took seven forms. | 1 Cor 15:35-49 – The versus here share description of the resurrected body, written by Paul. Verse 43 states the body is ‘raised in power.’ The chapter continues to describe the change of physical and spiritual, and that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God.The Book of Revelation is filled with numbers, including four and seven. The following are examples:Rev 4 – This chapter falls after the words of Jesus say to John ‘To him that overcometh will I grant to sit with me in my throne, even as I also overcome…He that hath an ear, let him hear…’ After this John sees four beasts, each with a different power in nature, that guarded the throne of God.Rev 5 – Past the fourth beast, John is then shown a book with seven seals.Rev. 6 – John watches as Jesus opens the seven seals that each was present in different forms. |

| ‘All is being dissolved, both the earthly and the heavenly’ | The destruction of matter, sin and the flesh are mentioned in the Gospel of Mary. | 2 Peter 3:13 – Teaches of Jesus promise of a new heaven and earthRev 21:1 – John describes a new heaven and earth |

| Mary is given information without the other disciples | The disciple Andrew and Peter are skeptical that Jesus share things without them present | John 20:18 – Verses that recount what happened to Mary in the morning after Jesus was not found in the tomb. |

| They began to go forth and preach the words Mary spoke | At first, the words Mary spoke fell idle to Peter and Andrew. Levi pointed out Mary’s worth to Jesus, and Peter’s temper. After this they preached this gospel. | Peter, one of the first called as a disciple with his brother Andrew, is attributed to two books in the New Testament. These books are filled with his letter to the early church. There are many verses previously listed where Peter’s letters contain the teachings of Jesus that came before his departing in the Gospel of Mary.1 Peter 3 – This chapter speaks of where Jesus was for three days. The suffering of flesh and how it will be judged after death and will live according to God in the spirit. |

Views Outside of the Text

Scholars will often suggest that religious text is inspired by earlier people or writings, including ideas outside that religious doctrine. The gospel authors in the New Testament are often restating scripture and claiming Jesus commonly quoted from the Tanakh. The Tanakh is Jewish scripture known by Protestants as the Old Testament, which belongs to a culture known for a long history of oral reciting to remember the teachings. Many religious cultures are said to have recited beliefs through generations before writings were kept. It is also theorized that Jesus’ life on earth, as a deity, was fulfilling the ancient prophecies of the Old Testament that one would come through the lineage of King David. However, it is the outside influence that is of interest in the section. Before the era of Jesus, the prophets stopped appearing on set for approximately 400 years after the writings of Micah. This absence of mouthpieces of Yahweh, God of the Old Testament, left outside influence a better chance to intermingle with those in the Jewish culture. For example, the Greek philosopher Plato, born around 428 B.C.E., has often been credited with inspiring the authors of the gnostic writings, which currently include the Gospel of Mary (Pricopi, 2014). It is easy to argue that the culture we are surrounded by can influence how we portray new concepts. Plato’s academy, or teachings of philosophy, expresses that what we perceive to see, and sense is different from reality and that a sort of illusion is at work. However, this is not a new idea of Plato’s era either. One could argue that Plato’s philosophy was influenced by the culture that inspired the Hindu teachings of Maya or the illusion of reality created by a god. Equally, it can be argued that Plato was inspired by the Jewish teachings, mainly if he lived after the writings of Micah and before the words of Jesus (which are supposed to be a reinstalment of the earlier teachings that predate Plato). Inspiration of thought does not prove teachings of understanding, only that it is the way a culture describes a previous thought. Take something simple, like how anthropologists have discovered how other cultures outside of the United States interpret color differently. As children in the United States, we learn that a specific color is identified with a name, like purple. However, as we learn more, we understand that there is more depth to creating shades of purple and that it is made from two primary colors, blue and red. Knowing the breakdown of purple does not change that it is purple. However, step outside of the United States, and one learns that not everyone in the world separates color the same way, and some do not separate color at all (Kay, 2018). For some cultures, the need to isolate and itemize color is not necessary to survive. The facts do not change that color exists and that people see shades of color; this example shows that perception and description can intertwine as other cultures influence us.What does the way color is recognized have to do with the Gospel of Mary? Simple perception. The stories represent the color purple, and the writings are perception, each viewed separately as they see the same thing. It would be easy to show that many religious writings were influenced, especially if the idea did not make sense to everyone. Not everyone who finds faith in a God understands the details of the message, and not everyone is a scholar.

Survey of who knows Mary

Outside of the scholars’ world, the general population also utilizes and reads the documents assigned to specific religions, even outside their own beliefs. Therefore, a survey was created through QuestionPro that initially set out to see what people knew about Mary’s name in the New Testament. How many Mary’s did they recognize? Had any of them read the Gospel of Mary? Equally, how the general readers view where the Gospel of Mary fits in their understanding of modern Christianity? Does the placement of the Gospel of Mary by scholars change their interest in this manuscript? Turns out more people are interested in what it says than not (over 60% willing to take the second survey and read the Gospel of Mary). The original sample was created from the public through a general social media post, a targeted post in specific groups that read Christian literature and have a better understanding of the Mary in the New Testament, and emails sent to Arizona State University students.The following charts and percentages represent 192 respondents surveyed (12 countries with 0 dropouts) about Mary of the New Testament. The survey was sent through the following:

- Facebook in a general post

- Facebook Tim Mackie bible discussion group

- Emails sent to Arizona State University students in Spring A Session (REL 406, ASB 102, ASB 394)

The sample population included the following:

- 66% Female, 31% Male, 3% Other

- Ages:

- 9% (35-44)

- 4% (25-34)

- 8% (45-54)

- 16% (18-24)

- 5% (55-64)

- 21% (Above 64)

- 4% Christians, 22.6% Spiritual, 9.6% Non-religious, 7% Other not listed, 1.7% Atheist, 0.9% Jewish, 0.4% Muslim

- 3% previously read the Gospel of Mary

- 88% have read the New Testament, 14.1% only hear it in church, 13.5% have not read the New Testament, 0.5% listen to the audio version

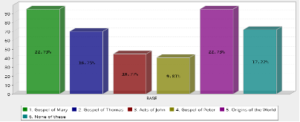

Which of the following is not in the New Testament?

| Mean : 3.447 | Confidence Interval @ 95% : [3.270 – 3.625] | Standard Deviation : 1.855 | Standard Error : 0.091 |

The survey did not add too much additional information on the Gospel of Mary, with only 6.25% of those surveyed had read it previously. However, the chart above shows a question posed to see if those familiar with the New Testament (71.9% have read it) are familiar enough to remember the names of the books listed in the canon. The correct answer was given by only 17.2% of the respondents, none of the options appear in the New Testament. A follow-up survey sent 153 people who agreed to read the Gospel of Mary and answer additional questions. This data could show that the words ‘gospel’ and ‘acts’ may have confused them, or the familiar names of Thomas, Peter, and John led them to believe they were a part of the New Testament. On the flip of this, the Gospel of Mary title contains a familiar name found in the canon stories and the term gospel, so this did not create the same confusion as with the male names. A further study may address this with a look at the perception of Mary as a female.

The data from the follow up survey: The data from the next survey did not produce a large enough sample size to establish proper statistical significance, but the data is only from those surveyed in the original sample. This survey was emailed and not posted on social media:

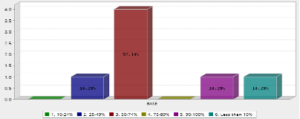

What percentage of the writing (in the Gospel of Mary) would have to be parallel in teaching of other texts (the Nag Hammadi Library) for you to accept that it belongs in the gnostic gospel category?

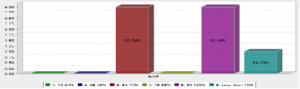

What percentage of the writing (in the Gospel of Mary) would have to be parallel in teaching of other texts found in the canonically accepted writings (New Testament) for you to accept it belongs in the Christian category?

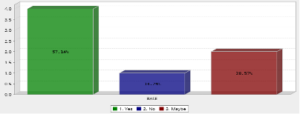

Do you believe that any of the early Christian teachings were lost?

Did you find any familiar teachings in the Gospel of Mary that are in the New Testament?

The second survey was sent out to 153 people, but not enough data was retrieved prior to this paper. Despite not having a large enough sample, what can be said about the current data is that 100% agree that there were female disciples that continued to preach Jesus’ message after his resurrection, but 33.3% state they believe female disciples were not considered an authority of Jesus teachings; 25% believe early Christians did not allow women to preach; 16.7% feel female writings were lost. Of those surveyed 57% (and 28.7% – maybe) found there was familiar teachings in the Gospel of Mary to the New Testament. The interesting stat is that 57.2% selected that they would only need 50-74% parallel teachings in the Gospel of Mary with the writings found at Nag Hammadi to consider it part of the Gnostic Gospels. However, a split occurred when asked the same question but with the Gospel of Mary and the New Testament; 42.9% for both 50-74% parallel and 90-100% parallel. According to those surveyed, the New Testament would need more paralleled teachings to accept the Gospel of Mary as a Christian text. Though these data sets will continue to change as more fill out their survey, it is interesting to see that people place more precedence on the standard of Christian teachings than non-canonical writings like the Gnostic grouping.

Analysis and Argument

Accurate placement is not always a guarantee when trying to access the enemy. The enemy in the Gospel of Mary could be several things, including content that questioned sin or the power women held in Jesus’ circle. Either way, with three separate manuscript fragments of the Gospel of Mary, it is evident that this writing was in circulation. However, something kept it from the rest of early Christian teachings. Was it the version of Mary who claimed to teach visions of Jesus? People can create divides quickly when the context of their surroundings is not applied objectively. Anthropologist E.B. Tylor possibly held a grudge against his experiences growing up in an institution of religion, as he later described religions as primitive. His assessment that religion is a stage of primitive thinking created a divide in how some viewed religion in his era, yet religion remains past the Era of Enlightenment. As researchers, it is not in our interest to speak in such absolutes about religion. The same can be stated about what falls in the category of the gospels of Jesus.

Therefore, it is plausible to state that as the New Testament was under construction, evolving over the centuries, there was a negation of textual acceptance of words and themes that did not fall in line with church leaders or ideas of that time, including the Gospel of Mary. Not that the manuscripts were not Christian, only that they did not fit the modern agenda. Cultures evolve, and origins can be lost. However, when history is found, it is vital to place artifacts where they belong correctly to understand their purpose.

The purpose of this study was to do just that, place the Gospel of Mary closer to teachings that are closer related than where it is placed currently. The Gospel of Mary’s explanation of sin and what happens beyond the veil mimics the themes and topics of Jesus in post-resurrection as depicted in the New Testament by several authors. It follows less of the Gnostic versions.

As the Christian church branched off as a separation from Judaism after Jesus came on the scene, but the religion kept the doctrine of the Tanakh, or Old Testament, from early Jewish history as part of its foundation of prophecy. The Gnostic writings are no different, taking textual ideas and philosophy of Jesus and other philosophical ideas in circulation during the mid-second century to understand the physical universe as an illusion and the spiritual world as reality. The Gospel of Mary does not appear to embrace this school of thought as it tackles other topics. It can be argued that the Gospel of Mary existed at least a century before the Gnostic movement, implying Mary’s words inspired come manuscripts attributed to Gnostics. Equivalently, with the end of the Gospel of Mary claiming the disciples went out and preached after she taught them, all the similar topics and themes in the New Testament can be attributed to this works origin story in the first century.

Many Gospel of Mary teachings find familiar topics and language used by authors of the New Testament. One influential author is Peter, who also is on the scene in the Gospel of Mary, opens with a question to Jesus about the nature of matter. The nature of matter topic was a common philosophical debate in the first century and arguably today (King, p.45). People want to know if matter pre-exists this life and does it continue to exist after we die? In the Gospel of Mary, Peter wanted to hear what Mary knew but quickly dismissed the strange teachings; however, evidence shows he and others went forth to preach these teachings. In 2 Peter 2-3, Peter taught what the Gospel of Mary proclaimed, including words that describe how evil’s nature would ‘utterly’ perish. Also, Peter’s letter to the early churches explains the importance of knowing Jesus removed sin from the world, as he explained in the Gospel of Mary.

One of the general statements found in the reading about the Gospel of Mary, for various sources, is the strange or unique teachings presented in the second half of the manuscript. The journey Jesus describes to Mary in the vision as the soul communicates with different powers and forms in order for the flesh and spirit to separate and ascend to the kingdom of God is not so strange when compared to John’s visions in The Book of Revelation. Reading from Revelation is like walking into Narnia and wondering who is playing the role of God as hybrid creatures wander the world guarding a throne. The end of chapter 3 in Revelation begins a journey towards God’s throne, but four beasts stand between it and an oceanlike veil, mimicking the four powers that Jesus described facing on his way to God. Past this point in Revelation, John was shown seven seals by Jesus, mirroring the seven forms described by Mary. The argument could be made that the New Testament claims show that Jesus did not go to Heaven immediately after he died (John 20:17 KJV), and we know the beginning of the Gospel of Mary is post-resurrection. However, Jesus did depart, and Mary gave the teachings of a vision in the next part. The counterargument is that ‘time’ between realms, where he was three days after he died, is not measurable or explained. Plus, when Mary tried to speak to the grieving disciples, there is no guarantee this was in the same setting or that the physical time she taught them was immediately after Jesus departed. Hours could have gone by before the next part of the teaching began.

The final piece that places the Gospel of Mary in the category of New Testament teachings is the carbon dating that could eventually date the two Greek fragments in the first century along with the other early Christian writings. The more specific this gospel manuscript is dated to the first century, the more it will push further away from the Gnostic movement that took off late second century. It may not prove important to modern-day Christians. Still, it will aid in studying how early Christianity evolved and what the people believed before the formation of the canonical collection. Religious studies and anthropology need to recognize how humans develop in religious culture to understand where we are headed as a human species.

Conclusion

This study set out to place a gospel attributed to Mary closer to the New Testament studies formed by history and away from the manuscripts tagged as Gnostic gospels. Instead of fitting with the gnostic groups, the Gospel of Mary manuscript reveals teachings from a vision and the words taught to the disciples by a tangible Jesus after he died physically, falling in line with the meaning of the term gospel. The Gospel of Mary does not keep the teachings of Jesus from anyone; it is clear the message is to be heard by anyone with ears, equally falling in line with the New Testament, and not the elite select of the Gnostic factions. Likewise, in the Gospel of Mary and the New Testament, Jesus took sin from the world, yet Gnostics do not operate under sin or the salvation of Jesus’ sacrifice for the world’s sin. The Gospel of Mary clearly states the nature of sin after Jesus’ death, and the individuals must now seek it on a personal level before passing through a series of four powers and forms when the physical body dies. Researching the levels of human energy still active after death may be an addition to this study later.

The possibility that carbon-14 dates in the first century could shift manuscripts will show support that Mary’s teaching of Jesus’ words belongs in the New Testament studies and not the Gnostic group. Until then, this study will follow updates from Cornell University as it applies new data curves to different timelines in the southern Levant region. The general populace seems to be interested in knowing more about Mary’s Gospel and how it fits in with the canonical teachings. Therefore, from this study, readers of the Gospel of Mary can weigh the evidence that this work can be found throughout the New Testament with parallel themes and proof that the words Mary taught were preached later by those who followed Jesus and her place in history is needed. Mary’s word gave birth to Jesus, while another Mary proclaimed that he had been resurrected, giving life to Christianity. Had no one spoke that the tomb was empty, the virgin birth story would not have importance, yet the canonical New Testament devotes no written work to a woman called Mary.

Bibliography

Bauckham R. (2006) Jesus and the Eyewitness: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. Pages 3-37.

Brakke, D. (2010). The Gnostics : myth, ritual, and diversity in early Christianity . Harvard University Press.

Bügler JH, Buchner H, Dallmayer A. (2008). Age determination of ballpoint pen ink by thermal desorption and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Forensic Sci. 2008 Jul;53(4):982-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00745. x. PMID: 18503526.

Byrne, R. and McNary-Zak, B.eds: (2009) Resurrecting the Brother of Jesus.The James Ossuary Controversy and the Quest for Religious Relics. Chapel Hill,NC: The University of South Carolina Press; pp. viii+215.

Chiavari, G., Fabbri, D., Galletti, G.C. et al. (1995) Use of analytical pyrolysis to characterize Egyptian painting layers. Chromatographia 40, 594–600 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02290274

Choat, M. (2019). Dating Papyri: Familiarity, Instinct and Guesswork1. Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 42(1), 58–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X19855580

Collector cleared of forging burial box of ‘brother of Jesus’. (2012, Mar 15). The Independent Retrieved from http://login.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/newspapers/collector-cleared-forging-burial-box-brother/docview/927951833/se-2?accountid=4485

Crotty, R. (2011). Resurrecting the Brother of Jesus. The James Ossuary Controversy and the Quest for Religious Relics – Edited by Ryan Byrne and Bernadette McNary‐Zak. Journal of Religious History, 35(3), 424–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9809.2010.01039.x

De Boer, E. (2004). The Gospel of Mary beyond a gnostic and a biblical Mary Magdalene. T&T Clark International.

Depuydt, L. (2010). Coptic and Coptic Literature: In A Companion to Ancient Egypt (pp. 732–754). Wiley‐Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444320053.ch33

Ehrman, B., & Plese, Z. (2011). The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations. Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

Ehrensvärd, M. (2006). Why Biblical Texts Cannot Be Dated Linguistically. Hebrew Studies, 47(1), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1353/hbr.2006.0039

Fletcher, R.E. (2003). Forgery Ring Suspected in “James Ossuary”; Israel Says Specialists May Have Conspired: FINAL Edition. The Washington Post.

Funk, Anna O. “From Scroll to Codex: New Technology and Opportunities.” Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet. 2015. CC BY-NC

Harris, S.L. (2015). The New Testament, A Students Introduction. 8th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hayes, C. (2012). Introduction to the Bible. New Haven and London. Yale University Press.

Holy Bible, King James Bible. (2008). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1769)

Kalman, M. (2012, Jul 02). Forged in Faith. The Jerusalem Report, 12. Retrieved from http://login.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/magazines/forged-faith/docview/1026667995/se-2?accountid=4485

Kay, P. (2018). Candoshi Color Terms. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 28(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jola.12178

King, K. (2003). The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the first woman apostle. Polebridge Press.

Manning Sturt W., Carol Griggs, Brita Lorentzen, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, David Chivall, A. J. Timothy Jull, & Todd E. Lange. (2018). Fluctuating radiocarbon offsets observed in the southern Levant and implications for archaeological chronology debates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, 115(24), 6141–6146. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719420115

Mazza, R. (2019). Dating Early Christian Papyri: Old and New Methods – Introduction. Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 42(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X19855579

Miller, R. J. 1. (1992). The Complete Gospels: Annotated Scholars’ Version. Sonoma, Calif: Polebridge Press.

Orsini, P., & Clarysse, W. (2012). Early new testament manuscripts and their dates: A critique of theological palaeography. Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses, 88(4), 443–474. https://doi.org/10.2143/ETL.88.4.2957937

Perkins, P. (2009). What Is a Gnostic Gospel? The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 71(1), 104–129.

Pricopi, V.A. (2014). Platonists and Gnostics on Negative Theology and Inner Self. Agathos: an international review of the humanities and social sciences, V (2), 21–30.

QuestionPro Survey (2021)

Robinson, J. (1977). The Nag Hammadi library in English (1st U.S. ed.). Harper & Row.

Shimron, Aryeh & Shirav, Moshe & Halicz, Ludwik. (2019). The Geochemistry of Intrusive Sediment Sampled from the 1St Century CE Inscribed Ossuaries of James and the Talpiot Tomb, Jerusalem. Archaeological Discovery. 2020. 92-115. 10.4236/ad.2020.81006.

Taylor, J. (2014). Missing Magdala and the Name of Mary“MAGDALENE.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 146(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1179/0031032814Z.000000000110

The Oxford dictionary and thesaurus. (American ed.). (1996). Oxford University Press.

The Pell Center. (2019, February 21). Karen King on Story in the Public Square. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M05hsMbRNKc

Tuckett, C. (2007). The Gospel of Mary. Oxford University Press.

Turner, E., & Parsons, P. (1987). Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (2nd ed., rev. and enl. / edited by P.J. Parsons.). University of London, Institute of Classical Studies.

Turner, E. (1968). Greek Papyri an Introduction. Princeton University Press.

Van Minnen, P. (2006). Saving History? Egyptian Hagiography in Its Space and Time. Church History and Religious Culture, 86(1), 57–91. https://doi.org/10.1163/187124106778787024

White, W. (2015). Isotope Geochemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.